Last week’s FOMC statement brought nervousness back into the market as the Fed hinted it might start with quantitative easing (QE) again. It is a fact that the three major central banks in the world, FED – BoE – ECB, are struggling in their fight against deflation and do everything they can to inject some inflation into the system.

As Alan Greenspan will go in history as the man who put a safety net under financial markets with his famous “Greenspan Put”, Ben Bernanke is working hard to become the Knight that fights Deflation. It would certainly be a great title for a cartoon and the best way to illustrate his future legacy in one picture would be as follows:

The very reason why the monetary authorities are still struggling with deflation is obvious. The deleveraging process which was put in motion from the beginning of the Great Credit crisis has not come to an end yet. The public has been put on a wrong footing with comments such as ‘green shoots’, given a false sense of illusion that the crisis could simply be put behind us via massive stimulus packages.

Before the summer of 2007, the global economy was performing on testosterone. In this case it was a shadow banking system that was flooding the market with cheap credit. This parallel circuit exploded via its leverage and has brought global demand back to new levels.

The first round of QE was trying to smooth out the shock that was caused to the system due to the Lehman collapse. This bankruptcy was only a cathartic event in a process that was built up more than a year before when the first subprime lenders started to go bust. As the US economy was fueled by an accommodative credit card industry and a leveraged housing market that functioned as ATM machines for US households, other parts of the global economy, for example Germany and Japan, were driven by a (cheap) credit fueled trade.

Governments and central banks stepped in to prevent the world falling off a cliff. To a certain extent the authorities have succeeded in kickstarting the global economy. At least inventories have been rebuilt, but now we are muddling through a New Normal as Mohammed El-Erian from Pimco described more than a year ago.

What did we learn from the first round of QE, and more importantly is a trip on the QEII worthwhile? Will a couple of trillion of extra USD into the system bring back the good old times? We doubt it.

Banks are still struggling with capital and Basel III. Although it turned out to be a compromise, it will keep banks under pressure to focus on more rigid capital ratios for the time being. In this respect extra liquidity is not the right answer to capital issues.

Will a couple of trillion of extra USD loosen up the lending standards among banks? Most probably not, since this was also one of the reasons that brought us into this mess in the first place.

Will a couple of trillion of extra USD bring back all the customers that went bankrupt? The answer is once again no, as they disappeared due to the over capacity that was created by the shadow banking system earlier on.

Figure 1 below also points out that in general banks simply put this money back with the central bank (in this case the Fed).

Figure 1: Fed total reserves, not adjusted for changes in reserve requirements

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve and John Mauldin

One can argue though if this money is not used by banks to lend among each other, how would or could this trigger inflation? This is a valid point. At this stage central banks are not successfully injecting inflation into the system via QE. As a consequence why inject another trillion dollars into the market?

The danger is though from the moment that there are signs the economy is recovering at a faster pace, this money will be (very) quickly used by banks and flow rapidly into the market. We have written on a number of occasions that central banks, and the Fed to start with, have a very poor track record in anticipating trend reversals.

Figure 2 US 2y Average GDP versus Fed Fund Rates

As Figure 2 illustrates especially the Fed has a tendency of overshooting its rate policy. During the 1970s and from 2001 onwards the Fed had a policy where it kept Fed fund rates systematically below average growth.

We know by now what the result of that was in the 1980s. Volcker and with him many other central bankers had to fight a period of increased inflation.

Such a Keynesian policy run the risk of intensifying great imbalances in an economy. Due to a mispricing of the cost of money, misallocations of capital take place which lead to boom and bust cycles as we have seen during the credit crisis of 1974 and more recently the Great Credit Crisis.

This is based upon the findings of the economist Ludwig von Mises who in turn further developed the theory of Knut Wicksell in the 19th century. He argued that a disequilibrium between general demand and supply on monetary prices are not temporal but cumulative. In simple terms, any deviation from an equilibrium sets off a dynamic process that continually leads the system away from the equilibrium. If for any reason, the general demand is set and maintained above the general supply, no matter how small that gap is, the consequence will be that prices will start rising and keep on rising.(1)

Both Wicksell and von Mises suggest that a central bank should occasionally keep its rate above the growth rate of the economy to smooth out the excesses or overcapacity in the economy. In this respect a recession should be self correcting. Or “recessions are nothing more but a natural consequence of a free economy created by the divergence between the natural rate and the market rate “ (2)

This is exactly what is worrying us with the Fed planning to go on a QEII cruise. Taking back one trillion USD from the first QE operation will already be a challenge as we are in uncharted territory. Imagine what could happen if this amount becomes USD 2-3 trillion.

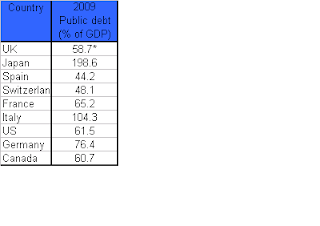

Therefore in a deflation versus inflation debate we remain convinced that an extended period of above average levels of inflation sooner rather than later will come to bear. Governments like the US-UK and certain EUR-zone members will not oppose against this as it would enable them to inflate away their outstanding debts.

At least the gold market is showing similar signs of worriedness. Bear in mind though, gold is usually not an ideal hedge against inflation. The underlying volatility is too high to keep it as a single asset against inflation in a portfolio. In this respect it would be sensible to look for alternative hard assets to protect ones capital against the erosion of inflation.

1. Wicksell “Interest and Prices”, p. 101, 1936 Augustus M Kelley Pubs

2. Charles Gave and Louis-Vincent Gave, “Ricardian Growth, Schumpeterian Growth and the Cost of Capital.” Sept 15 2010, Hong Kong